Pope kicks off 7-day

Pope kicks off 7-day

marathon Bible reading

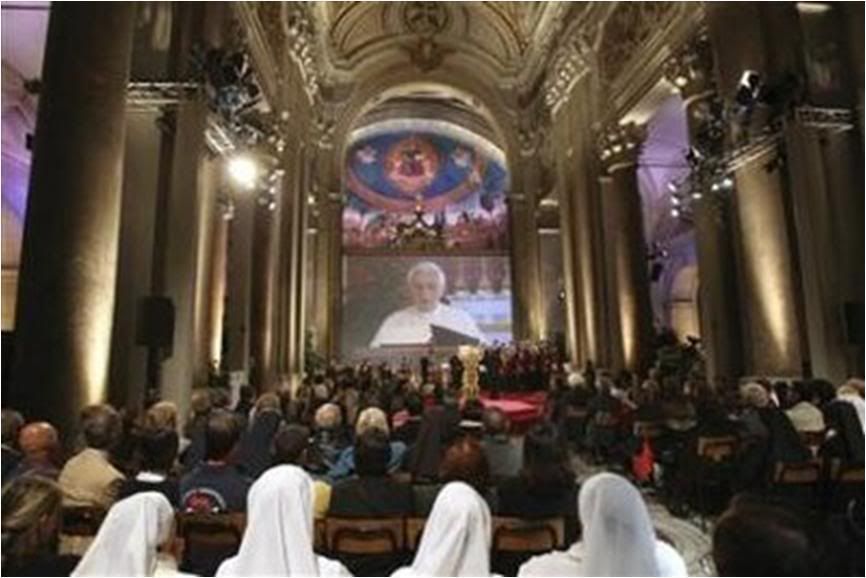

ROME, Oct. 5 (Reuters) - Pope Benedict on Sunday kicked off a seven-day, non-stop Bible reading marathon on Italian television.

The Pope read for several minutes from the start of the Book of Genesis live from his apartments in the Vatican while other speakers read in the Basilica of Holy Cross in Rome.

In the next seven days and six nights, more than 1,200 people will read from the Bible until all 73 books of the Catholic edition is finished.

The second reader was from the Russian Orthodox Church and the third was an Italian protestant leader. Others on the first night included Italian politicians and artists, among them Oscar-winning actor and director Roberto Benigni.

Tenor Andrea Bocelli sang between readings.

Rome's chief rabbi, Riccardo di Segni, had originally agreed to read immediately after the pope but pulled out of the event last month, saying it had become "too Catholic."

The broadcast began live on state broadcaster RAI's first channel and was to continue on one of its satellite channels.

Reflections on Bible reading

Translated from

the Italian service of

Amedeo Lomonaco interviewed Mons. Gianfranco Ravasi, president of the Pontifical Council for Culture, about the Bible-reading marathon on Italian TV which started tonight:

MONS. RAVASI: The Bible presents itself as the Word, and the Word by its nature is proclaimed, said. That's the importance of returning to the Word, and in this case, to make this Word resound, syllable by syllable, entrusted to the voice - I would say to the entire spectrum of possible voices, which are the voices of mankind. This Word that resonates and breaks the silence of nothing, which opens us to being and existence.

We know that a word, once said, is not dead - that is when it starts to live. That is why ideally this reading should be like a point of departure - because the Word has to go through the polluted skies of our cities, it must cross - ideally - all our streets, enter into our homes and return to being what the Bible itself says of itself: a Word that is 'offensive', that causes unease, that undermines even superficiality, banality.

Jeremiah says, "My word is like a hammer that breaks rock" - the rock of incrustations, of banalities we would say today.

And so, here we are to recover this Word which we shall make resound for once in its entirety under the vault of this Roman Basilica, that it may be a lamp beneath our feet in our journey of life.

For the person who has never come near the Bible, the exhortation is to relive the experience of St. Augustine whose conversion came with that 'Tolle lege' - take it and read.

Yes, that's true. We can use it as a motto. But of course, it also means one must start all over with an itinerary to follow. Taking the Bible and opening it at random to any page is not at all the correct thing to do, even though sometimes it can be sort of a stimulus.

What is needed is for this 'take it and read' to have a certain continuity, with some seriousness and faithfulness. The appeal we are launching [with the Bible reading event] is merely that of seeking as much as possible to reach the Word with one's own continuous and constant knowledge, and one's continuous and constant life experience.

In this exploration, to read and scrutinize the Bible is to place oneself before God in an attitude of openness, without judging the Word which is inspired by God,but allowing oneself to be guided by the Word ....

Let us be guided by the Word, but the Word must be understood, it must be penetrated with human ability, with personal freedom.

There is a very beautiful statement in the Apocalypse which can summarize this: "Here I am, knocking at the door. If someone opens it, I will come in, I will dine with him and he will dine with me".

Christ goes through the streets of the world, his Word too, and if it does not, then we will be alone in this world, in our small finite horizon. But what is indispensable is - "If someone opens the door to me': that is where freedom comes into play, freedom to receive the Word.

If one wants it, there is grace which, as Paul says, lights up the heaven in our life and is God's absolute primacy. But there is faith, which Paul says is man's response. In this encounter, this weaving together, is all the mystery of the Bible and of Revelation.

However, also yesterday, Mons. Ravasi, a well-known Biblicist among his many qualifications, wrote an essay for L'Osservatore Romano about the right approach to the Bible. Here is a translation:

The pentagram of Biblical verbs

by Gianfranco Ravasi

President

Pontifical Council for Culture

Translated from

the 10/5/08 issue of

"Is it not extraordinary that the Bible and its language speak to everyone everywhere? Why do these words never become boring? Where can we find a story so old about a small group of people in a foreign country, who only needed to be written about in order to obtain the gift of ubiquity?"

It was not a spiritual author who evoked the unexhausted and inexhaustible message of the Biblical Exodus in such passionate terms, but a Marxist philosopher, Ernst Bloch, in an essay with an evidently provocative title,

Atheism in Christianity (1968).

Of course, it is true that he then adds: "Or better yet, these words are boring always and only when they are spoken of to say they have been heard."

Perhaps it is precisely in this 'sentito dire' ('we have heard' or 'it has been said'), that is, a pallid and banal knowledge, though strewn over sacredly with mediocre incense, or secularistically varnished with low-brow sarcasm, which makes the Bible boring, something like a useless old sword.

In fact, to get near it and seize it with the hands, one risks discovering that it is a red-hot iron that burns, as Bernanos warned.

On the eve of this Bishops Synod that is dedicated to the Word of God, we wish to propose a sort of lexicon - very simple and free - of decisive Biblical verbs, but not according to lexicographic criteria of their textual occurrence nor the spectrum of their semantic value.

There emerges a pentagram capable of making us grasp the 'harmonic inspiration', both divine and human, in these pages.

Pages of a book -

Biblia, in Greek - which are the 'books' par excellence, are nonetheless the narration of a story which, with the famous essay

The great code by Northrop Frye, we can articulate in seven acts: creation (space and the cosmos), exodus (time and history), law (morality and sin), wisdom (existence, love, and evil), prophecy (truth and justice), Gospel (Christ, the Apostles,Church) and Apocalypse (resurrection and eschatology).

Before the Book, however, is the Event, the Word-Deed that tore open the silence of the void.

Our first verb will be the divine 'to say' -

amar in the Hebrew Genesis: "God said 'Let there be light, and there was light' (1,3), the Logos of the Johannine prolog: "In the beginning was the Word (1,1). A speaking that is effective, creative and redemptive, such that the God of the prophets sealed his oracles saying

dibbartî we 'asîtî, "I have said it and I will do it" (Ezechiel, 37, 14).

Dabar, in Hebrew, is not just 'word' but also 'act, fact, event'. On Sinai, Moses reminds us: "The LORD spoke to you from the midst of the fire. You heard the sound of the words, but saw no form; there was only a voice" (Deut 4,12).

The Lord is par excellence the Voice who speaks even in silence, if its true that on Sinai Elijah would discover the divine presence in a "voice of subtle silence' (1 Kings 19,12).

The Bible, then, before being

graphè/graphaì, 'Scripture/Scriptures', is the 'proclamation' of a word,

miqra, as Jewish tradition calls it, using the same root that would give its name to the Quran, the 'proclaimed reading' of Islam.

It is the Christian kèrygma, the voice of the evangelical herald who should cry out from the rooftops what it has learned in church (Mt 10,27).

That is why, more than being

'mala dizione' (bad diction), the sloppy and dragged-out liturgical reading that has been done from our pulpits is a malediction, a curse. The Bible is a living word, cutting like a sword and threatening like a hammer, which requires embarking onto new information channels (now about to migrate fully from the printed page to the electronic screens, from the cobblestones of cathedrals to the hairshirt of the new communications).

Its great narrations should resonate, with the sumptuous apparatus of their stories, parables and symbols, in a society without memories, often relying only on empty soundbite messages.

Using a bit freely a Platonic image (the philosopher was partial to the authentic 'to say' of the teacher, the 'to write' of the erudite), we are in a time of 'the shells of Adonis', where seeds are cultivated in scant soil that can only bear thin and frail twigs.

The Biblical Word is, yes, a microscopic seed such as the mustard seed, but aims to grow to a majestic tree in the horizon of history. Not for nothing did this Word, for centuries, nourish Western culture, of which it had become almost the 'code' for artistic and ethical references (think of the 10 films of the Decalog by Kieslowski*) - it is 'the great iconographic atlas', the first symbolic lexicon, "the colorful alphabet into which painters have dipped their brushes" (to use a glorious expression by Chagall), the 'well-tempered' instrument of the most elevated European music.

Shema' Jisra'el, "Listen, Israel!", is the great cry in Deuteronomy (6, 4) which constantly pervades the life of the faithful whose motto is the words themselves of Christ in the Fourth Gospel: "Whoever belongs to God hears the words of God; for this reason you do not listen, because you do not belong to God" (Jn 8,47).

The emblematic figure of the believer is Mary who, as Luke notes (2,19), "kept all these things, meditating in her heart" the word-events that opened up before her, meriting one of her Son's beatitudes, "Blessed are those who hear the Word of God and observe it" (Lk 11,28).

Just as the divine and human 'to say' is effective, in which "a word said is not a dead word but one that is ready to live" - as the American poetess Emily Dickinson put it - so also God's 'to listen', 'lending his ear' to the supplication of his faithful, is active and operative.

That is why in Italian, the 'ab-surdity' of a situation arises from the

sordita (deafness) of human intelligence, because listening is decisive in communications.

Because of this, another poetess, the German Nelly Sachs, invited us to 'unclose the ear', liberating it of the obstructions of chatter, to allow the prophetic Word to effectively exercise its own offensive (pro-active) capacity to undermine the terrain of superficiality and habit: "If the prophets burst through the doors by night,/ slashing wounds in the fields of habit,/ if the prophets burst through the doors at night,/ seeking an ear as their homeland,/ the ear of man, obstructed by nettles,/ then you will listen!"

To educate in listening - an intellectual and emotional activity which is anything but simple, above all in a world like ours made up of images, of strong impressions, of distracting noises, and the background buzz of electronic communication - becomes an indispensable exercise.

Only listening can activate the divine dream sketched by the prophet Amos: "Days are coming, says the Lord GOD, when I will send famine upon the land. Not a famine of bread, or thirst for water, but for hearing the word of the LORD" (8,11).

Intimately correlated with 'to listen' is 'to understand' which, it is known, in Biblical language but even in modern 'gnoseology', is not confined to the brain, that is to say, it is not merely intellectual rationality, but also embraces the will, sentiment, passion and even action (it is likewise well-known that the typical Biblical verb 'to know',

jada'/ghinòskein, also designates the sexual act between two persons "who know each other' through love).

True knowledge, in fact, is not merely 'informative' but 'performative' - it transforms and transfigures, giving rise to

hokmah/sophìa, 'wisdom', which is much more than mere cultural equipment and erudition, but the Latin

sàpere, "to taste', to be endowed with a global and comprehensive symbolicity, a 'flavorful knowledge' to use an expression of the philosopher Jacques Maritain.

It is in this light that one can explain (certainly not according to gnostic indications) the famous statement of Jesus in the Johannine gospel: "Now this is eternal life, that they should know you, the only true God, and the one whom you sent, Jesus Christ" (17, 3).

At this point, we should lay on the table the complex question of Biblical hermeneutics, to which we can only allude briefly. It is significant to note that medieval tradition (of which Dante is an extraordinary witness) tried to dam up the 'overflowing significance' of the sacred Word - to adapt an expression of the critic Carlo Ossola - within the famous four hermeneutic registers called the spiritual 'senses' par excellence - the literal, the allegorical, the tropological, and the anagogical.

This practice already showed then how impoverished was the 'literalist' way which chained the Word to fundamentalism, ignoring the richness of a Logos which is eternal and infinite, even if anchored and intimately woven into the

sarx, the 'flesh' of the 'letter', of history.

It is precisely in this perspective that, in the assault on and struggle with the divine Word in order to understand it (the image is from the medieval Rupert of Deutz), Biblical interpretation should go above and beyond the separation - not to mention antithesis - between history and faith, between historico-critical method and theology, between symbol and truth, between philological research and pastoral use, between the academy and the pulpit, between scientific exegesis and spiritual reading.

In an essay entitled

Biblical interpretation in conflict, the then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger lamented a kind of 'hiatus between exegesis and dogma' which extended to ecclesial life, and which urged a response to the question that John Paul II had proposed to the Church when he wrote in

Tertio Millennio adveniente: "To what extent has the word of God become more fully the soul of theology and the inspiration of the whole of Christian living, as

Dei Verbum sought?" (No. 36).

Yes, because that Conciliar Constitution showed active interest in the ecclesial, 'apostolic' aspect of the exegetical task, without thereby abdicating the rigor of a critical approach: "Catholic exegetes then and other students of sacred theology, working diligently together and using appropriate means, should devote their energies, under the watchful care of the sacred teaching office of the Church, to an exploration and exposition of the divine writings. This should be so done that as many ministers of the divine word as possible will be able effectively to provide the nourishment of the Scriptures for the people of God, to enlighten their minds, strengthen their wills, and set men's hearts on fire with the love of God" (No. 23).

A great teacher of exegesis like the Jesuit Luis Alonso Schökel was right when he observed that "the study of the Bible runs the risk of becoming a science not of the Bible but of the scholars. But the Bible was not written for scholars. Besides, to know all the data regarding a text is not yet to understand the text".

It is therefore necessary to re-acquire a real hermeneutic equilibrium between indispensable critical analysis and the 'canonical' synthesis of the sacred Book, with the Bible itself as the final inspiration, because for all its real historico-literary multiplicity, it remains a unitary synchrony of the Divine Word.

In this light, the figure of Christ becomes capital as the true and proper guiding thread that runs through the Bible. this is evident, not only through an extrinsic and allegorical listing of the pre-figurative texts present in the old Testament, but rather through the rediscovery of the compactness of the dialog between God and mankind - God who, as the Letter to the Hebrews notes - "In times past, God spoke in partial and various ways to our ancestors through the prophets; in these last days, he spoke to us through a son" (1, 1-2).

Christ seals a discourse that was distributed over time and delineated in the Sacred Scriptures, and it is in the light of this seal that the words of Moses and the prophets retrospectively acquire their 'full sense', as Jesus himself indicated on that spring afternoon as he walked from Jerusalem towards the village of Emmaus in dialog with Cleophas and his friend, explaining to them "everything written about me in the law of Moses and in the prophets and psalms" (Luke 24, 44-49).

In order to hear/understand authentically the proclaimed Word, it is therefore necessary to unite the Letter and the Spirit, the memory of events and their salvific attestation, historico-critical analysis and revelation, in the full sense that can be achieved by the 'Spirit of truth' which "leads to truth in its entirety".

It is necessary to intersect the 'genetic' (from Genesis) movement which brings us to the original substance of events and Biblical texts, and the 'destinational' movement, to use the technical term, that is, the capacity of these texts to apply to the present.

Yes, because every genuine interpretation cannot be content with an 'centripetal' itinerary which goes back to the origin of facts and acts and generative recounting of sacred history to isolate, identify and weigh them, but it requires a 'centrifugal' direction as well ,which leads from the core to the periphery, that is, to us today, to the actual existence of the person who listens to and reads those memories.

So too, it is through this double process that inculturation of the Biblical Word must develop in different cultures. It is at this poibt that the third verb in our pentagram takes shape.

TO BE CONTINUED

BIBLE-READING MARATHON

IS OFF AND RUNNING

Following pictures taken at the Basilica of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, Rome:

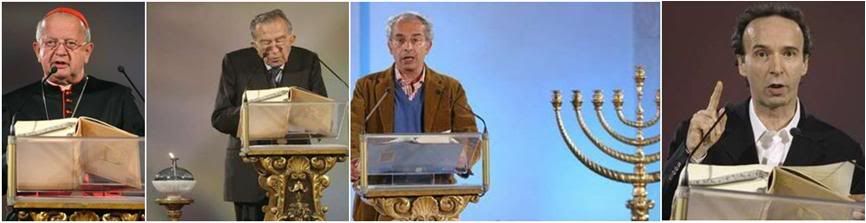

Among those who read last night: Cardinal Dsiwisz, Giulio Andreotti (6-time Italian Prime Minister, senator for life and publisher of 30GIORNI), Jewish-Italian journalist Gad Lerner, and actor Roberto Benigni.

Among those who read last night: Cardinal Dsiwisz, Giulio Andreotti (6-time Italian Prime Minister, senator for life and publisher of 30GIORNI), Jewish-Italian journalist Gad Lerner, and actor Roberto Benigni.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 06/10/2008 16:22]